Crass in Context

It is a few years ago now since I discovered that my daughter was learning about the women's peace camp at Greenham Common in her school history lessons.

"History? How can it be history, your mum was there!"

She just gave me a dismissive shrug and carried on revising.

The economic change brought by the Revolution is only the first of our demands. We will not be content with anything less than the total annihilation of existing reality and the total triumph of Desire.

Penelope Rosemount London 1966. [from King Mob Echo : Vague 31: Dark Star / AK Press: 2000 page 13]

One of the myths of punk, indeed its very foundation myth, is that 1976 was Year Zero. That punk sprang like a weird alien mutant birth out of the bloated belly of progressive rock, in the process destroying everything that had gone before. But it didn't really. If you read carefully through the first parts of Jon Savage's England's Dreaming (still the best book on punk), you can find the elements out of which it was constructed.

It was almost a Hegelian process of thesis: antithesis: synthesis. Rewind ten years from 1976 and there is 1966. 1966 was a point where the 'revolutionary' phase of sixties popular culture got going - out of a mixture of politics and drugs and a mass market for 'youth culture'. [ At least it was in North America and North Western Europe - hardly had a great impact for most people in most of the world]. A summing up slogan is one from Paris in 1969 "We take our Desires for Reality because we believe in the Reality of our Desires".

Lots of firework rockets went up and lit up the sky in a blaze of psychedelic colours before falling back to earth as burnt-out sticks as the seventies began. Or as The Pop Group were later to put it 'Escapism is not Freedom'. Rock music, for the survivors, managed to turn rebellion into lots of money. David Bowie's 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars summed it all up. Bowie was a sixties veteran, but his re-invention (like that of Marc Bolan and even, if briefly, Lou Reed) as a 'glam rock star' appealed to a new generation.

Anthropologists and historians talk of 'cohorts' and 'age sets'. By this they mean a group of people who move through initiation ceremonies/ rights of passage/ shared socialisation together as a generational group. So the sixties were significant for a UK 'cohort' who shared Elvis and the Beatles/ Stones as initiations/ rites of passage from adolescence into adulthood. But by 1972 Bolan and Bowie , although of that generation, were adopted by a next cohort of adolescents and it was this age-set for whom punk in 1976/7 was to become their rite of passage into adulthood. For this generation, the sixties were part of their childhood.

But, and this is an important but, Vivienne Westwood, Jamie Reid, Bernie Rhodes, Malcolm Mclaren etc were of the sixties cohort. This allowed for a process of cultural evolution. They did not replicate the cultural revolution of the sixties. They reproduced it. Replication produces carbon copies, clones of the parent material. Reproduction (in biology achieved via sex) mixes up the parent material, creating something similar, but different. In nature, Darwinian survival then weeds out the non-viable variations and multiplies the viable ones.

But whereas genetic evolution is 'blind', cultural evolution is self-aware, is conscious of its actions. It is intentional. This seems to be what Debord was getting at with his emphasis on the importance of historical consciousness in The Society of the Spectacle. The Spectacle survives via replication of one particular historical moment - that of the bourgeoisie revolution. It is a so far successful attempt to 'freeze' history and thus prevent cultural/ social evolution.

Cultural evolution (change) keeps trying to happen, but the Spectacle keeps recuperating change via the mass media so what we get is the illusion of constant change whereas the structural reality of everyday life remains forever the same.

It has been argued [Stewart Home] that punk was not directly based on situationist theory/ practice. This may be true. However, situationist ideas and slogans were part of the late sixties revolutionary mix and these were folded into the creative chaos which became punk. In turn, what were tired old clichés for the sixties cohort were found as brand new and still revolutionary by the seventies cohort as they moved from glam rock to punk rock. Even for someone like myself, who had connected with the remnants of the sixties counterculture as still promoted by groups like Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies, the realisation that punk was (apparently) the creation of people my age - i.e. 18 in 76 - was a dramatic shock. It was the difference, as the Clash put it, between looking backward or looking forward.

But then, as ever with Spectacular Society, the recuperation of the revolutionary explosion began and what had been dangerous was made safe. But before it could be made safe, the Energy of Desire had to be Exploited - had to be turned into money. Which meant punk on Top of the Pops and in the mass media. Which exposed punk to a next cohort of 12 and 13 year olds and so set the scene for Crass...

Meanwhile, back with the dying embers of the sixties cohort, the free festival and traveller scene was developing. Confusingly for neat histories, this took place in parallel and apparent cultural opposition to punk. Part of this came from the post-sixties counterculture retreat from the cities - the communes movement, the early green/ radical/ alternative technology movement. George Mackay covers this in his book Senseless Acts of Beauty, - Ch. 1 the free festivals and Fairs of Albion. The magazine Undercurrents which existed from 1974 to 1980 documented this 'rural' development of countercultural practice and theory. Where it overlapped with popular rock music culture was at Stonehenge.

Where it connected back politically with the sixties was with the revival of the nuclear threat following the election of Thatcher in the UK and Reagan in the USA. This led to a revival of CND and mass opposition to the threat of thermo-nuclear genocide. It was this stark politicisation of everyday life which provides the context for Crass. Their anarcho-pacifist stance harked directly back to that of the more radical elements of CND in the early sixties - but was perceived as fresh and new by a post-punk generation.

It was a form of absolutism, as was the contemporary emergence of the Greenham Common Women's peace Camp and the many other similar Peace Camps which sprang up outside nuclear bases around the UK and across Europe. In the USA, there was the very different form ( but structurally similar) emergence of eco-feminism expressed by Starhawk in her Dreaming the Dark published in 1979. The question the Greenham Women posed was "Which side are you on?" .

Either you were with the nuclear warriors or against them. With the forces of death and destruction or with the forces of life and creation. In this context the ambiguities of earlier punk, its simultaneous evocation of creation AND destruction could not be sustained.

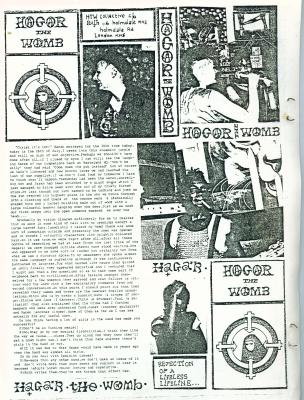

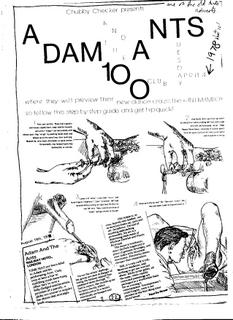

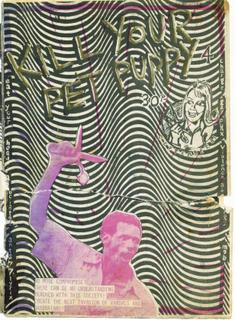

You can see the shift happening -in the first issue of Kill Your Pet Puppy for example. A shift from the 'decadence' of the pre- pop Adam and the Ants to the puritanism of Crass' 'Shaved Women' . The contrast between Frankie Goes to Hollywood's 'Relax' and their 'Two Tribes'.

It was, in historical terms, a fleetingly brief moment- from 1980 to 1984. A moment when any one with eyes to see gazed into the abyss of a nuclear holocaust. Life or death. A future or no future. Which side were you on?

For the duration of that moment, for a time when the existence never extended more than four minutes into the future, the totality of experience that was a Crass gig made sense, was reality. But even within those four minutes, the cultural explosion of other futures still existed and was only partially contained. By Stonehenge 84 this fragmentation and break up of what had briefly appeared as an intensely coherent 'anarcho goth punk' scene had already occurred.

What may appear from the perspective of the present to have been a 'golden age' of political engagement and activism was in reality created by the fear of imminent extinction.

Part Two : For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder?

Sounds like a Crass song title. But it ain't. Title of 1980 album by The Pop Group. Just pulled it out from the stack of (vinyl) records which I frequently play. Still vibrant, exciting, direct, challenging after 25 years. The Pop Group tackled similar themes to Crass, but managed to fuse the rhetoric with the music in a way Crass rarely did. I had to put the record on after picking up George Mackay's Crass chapter in Senseless Acts of Beauty.

1980 also saw the release of the Dead Kennedys Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables. The Pop Group may not have been 'punk' by the Kennedys absolutely were. And again they tackled political issues in a head on ferocious onslaught way... "killkillkillkill kill the poor..." / Holidays in Cambodia/ California uber Alles.

For alienation and existential angst, for the bleakest vision of a UK in decay, there is Joy Division -Unknown Pleasures. She's Lost Control - still sends a shiver down my spine. I saw Joy Division in 79 and again in 80. As an experience, Joy Division were far more 'disturbing' than Crass. My memory of Crass gigs is of them being almost cheery sing-alongs - with the whole audience joining in on the choruses of songs like "Do they owe us a living" or 'Fight war not wars'. If there was tension, it came from the threat of attack by BM skins, not from the music. Joy Division gigs were no less intense than Crass ones, but no one sang along with Ian Curtis.

But what about the barrage of contradictions, the films and banners, the presentation of the future as a nightmare [Mackay/1996/ 89]?

Throbbing Gristle. Cabaret Voltaire. What was to become 'industrial' music. Throbbing Gristle in particular created a 'corporate image', were a 'brand' and thus had a strong image and identity - were a product. For TG, the idea was to hold up a mirror to industrial society, to corporate/ consumer culture, to the media. TG did not produce records, they produced "annual reports", they structured themselves as a corporate entity, with Genesis P. Orridge as CEO.

TG never fitted into punk, they were too subversive, too knowing, too clever by half. Yet their trajectory ran parallel with that of punk and [see Ripped and Torn 18 scans below] were rated by Mark P. for their 'massive contribution to everything'. But was anyone in Crass aware of Throbbing Gristle? That is an interesting question - but not one I can answer.

What did notice at the time was that Psychic TV [ post Throbbing Gristle ] picked up a strong support base from among the Crass generation of punks. This would have been 83/4. [See my 1983 Diary of an anarcho goth punk fiend blogged here a few months ago].

To conclude this section - Crass were not unique in their all out assault on consensus reality/ society. In the critical 79/81 period, there were several groups who made/ used music and performances in this way.

So what was different about Crass?

Made in 1967, but immediately banned by the BBC, the drama-documentary The War Game was dusted down (by CND?) in 1980. It was shown in village halls and community centres up and down the country. I saw it in a community centre in West Hampstead round about then. The very fact that it had been banned made it more important- that this was the 'truth about nuclear war' that the state wanted to keep hidden.

Sasha Roseneil [Disarming Patriarchy; Feminism and Political Action at Greenham Common: Open University Press: 1995 : Chapter 2 : The Origins of Greenham] gives a very detailed account of how Greenham emerged 'as a social movement'. That the women's peace camp was supported by a world wide web of women, which in turn had been created by the growth of radical feminist networks through the seventies.

The wider anti-nuclear/ peace movement was likewise highly dispersed. Following the initial Women for Life on Earth's walk from Cardiff to Greenham in 1981 (inspired by a women's walk from Copenhagen to Paris organised by Scandinavian Women for Peace) several similar walks took place in the early eighties - although these were mixed ones. There was one from Feline to Greenham, another from London to Sizewell, which was followed in 1985 by a march from Sizewell to Molesworth. As these walks criss-crossed the country, they were supported (given places to stay, fed etc) by this dispersed anti-nuclear/ peace movement.

Parts of this support network can be traced back to the sixties and CND. For example, when Pinki returned home from London to Gloucestershire in 1980, she studied for A levels at Stroud Technical College and joined Stroud CND. This was a very active branch of CND. Barry Miles in his book 'In the Sixties' [Jonathan Cape: 2002] gives some background to this. Miles was a student at the Stroud branch of Cheltenham Art College between 1959 and 1962 and it seems to have been a lively centre for the UK's beat generation. Some, like Miles, moved on to London. Others stayed.

The early eighties revival of a nuclear threat coupled with the right-wing ideology of Thatcherism re-energised significant numbers of the sixties radical cohort. This meant that there was a strong grass-roots network through which the War Game moved, through which the anti-nuclear marches could move and - I suspect- which allowed Crass unprecedented access to performance spaces far beyond the traditional rock gig circuit.

It is also significant that punk managed to disperse itself so widely. It is difficult to quantify, but the impression I have was that every town and village in England (and Scotland, Wales, Ireland) had their own punk band and or/ fanzine. It was the DIY aspect of punk, the belief that anyone and everyone could form a band, put on a gig, produce a fanzine, make their clothes, which was its most important effect. The plethora of independent record labels and fanzines also allowed hundreds of small record shops to exist. The fact that even 'mainstream' punk records were hard to find outside of major cities helped this development.

Did Crass connect across the generational boundaries between the sixties and the eighties radicalised cohorts? That would need a bit more detailed research. I only went on the 1985 Sizewell to Molesworth peace march/ walk. It was Pinki who would have been able to answer that question straight off. Certainly I don't recall the 1985 walk having many/ any Crass fans on it. The activists came from a different cultural context - Quakers, greens, ex-sixties CNDers, feminists, Peace Pledge Unionists, 'hippies' (i.e. blokes with long hair and women with long peasant style dresses), Campaign Against the Arms Trade - the parents or older brothers and sisters of punks/ Crass fans.

Or with Stop the City - Dave Morris and London Greenpeace were the main motivators and organisers, the anarcho-punks just turned up on the day. The more I think back, the more I can remember, the clearer the distinctions. The anti-nuclear/ eco-activists community of the early eighties were an older group than the people who went to Crass gigs, who were the anarcho-punks.

If the Crass cohort had an impact, it was in the late eighties/ early nineties, as they moved from being teenagers into their twenties.

SO MANY PROBLEMS, SO MANY CAMPAIGNS

Too much happened. The Miners Strike. Wapping. [But which were mainstream] There was the whole Stonehenge Campaign from 1985 onward, which overlapped with the campaign against the Criminal Justice Bill which set out to criminalize squatting and travelling. Which then got mixed in with acid houses raves and the attempt to criminalize 'repetitive beats'. Then the Poll Tax. Then the anti-roads campaigns and another Criminal J justice Bill. And the first Iraq war campaign. And the Diggers/ This Land Is Our Land actions .And Reclaim the Streets, the carnivals against capitalism, and on and on and on. G8. Not to mention Support the Handloom Weavers campaign - or was that 1793 ?

To conclude for now. There is a constant and continuing level of direct political protest and action going on all the time. Day in day out, it is a background noise of dissent which rarely makes any more than local news. It is part of the structure of social reality.

Every so often some especially stupid act by government or business pours petrol on the smouldering embers and there is a dramatic blaze of protest and resistance. In 1979, the hotting up of the Cold War with new missiles placed in Europe fuelled just such an upsurge. It was very powerful and dramatic since the threat was so widespread. It suddenly occurred to millions of ordinary people that these lunatics (Thatcher and Reagan) were prepared to blow us all up in the name of freedom and democracy.

Across Europe there was a wave of actions and protests and campaigning and noise. The upsurge even managed to break through the usual barriers which keep political protest out of popular culture. There really was a mass-mobilisation against the threat of thermo-nuclear genocide.

The threat passed, the protestors de-mobbed themselves and the activists got back to their everyday campaigns. However, as the wave of popular dissent ebbed away, it left a few strange iconic symbols in its wake - just as the sixties gave us the CND symbol.

In this case, the Crass symbol and the circled A. And a Memorial Garden at Greenham. As we forget, so these symbols become mysterious. What was it all about? Who were Crass? What was a Greenham Woman. Soon even these questions will fade and it will be as if no-one of it ever happened. And none of us ever existed.

The Eighties? Duran Duran and Dallas...