greengalloway

As all that is solid melts to air and everything holy is profaned...

Thursday, March 29, 2018

Friday, March 16, 2018

Gaelic, the Wars of Independence and Galloway

This could get complicated. In September there will be a one day conference on Gaelic in Galloway. I will be giving a talk on the shift from Gaelic to Scots as the language of Galloway.

The complications arise because the Gaelic of Galloway is only know to us through the evidence of place names and personal names. The only other evidence is a Gaelic song Òran Bagraidh which has some Galloway place names in it. However, it was first collected in North Uist in the nineteenth century which means we cannot be certain that it was originally composed in Galloway.

|

| From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galwegian_Gaelic |

Looking for an alternative approach, I have been thinking about the history of Galloway in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This was a period when Galloway was caught up in two dynastic struggles. The first began at the end of the thirteenth century when two families with strong links to south-west Scotland were in competition for the Scottish crown.

The first struggle began in 1286 when the Bruce family carried out a series of savage surgical strikes on the Balliol family’s assets in Galloway from their lands in Carrick (south Ayrshire) and Annandale (east Dumfriesshire). This struggle lasted for 70 years, ending in 1356 when Edward Balliol gave up his claim to the Scottish crown previously worn by his father John.

The second struggle followed on from the first and involved the Stewart and Douglas families. Robert Stewart married Robert Bruce’s sister and so was king David II’s uncle and -since David remained childless - his heir. James Douglas was Robert Bruce’s most loyal follower and his illegitimate son Archibald (‘the Grim’) was loyal to king David- but not to Robert Stewart. The Douglas/ Stewart struggle continued until 1455, when Stewart king James II drove James, the 9th earl of Douglas, into exile in England.

What effect did these conflicts have on Galloway? A significant effect was to slow down or even reverse the assimilation of Galloway into Scotland. One consequence of this was the survival of Gaelic in Galloway long after Scots had become the dominant language in the rest of southern Scotland.

Galloway’s first and last independent king, Fergus, had died in exile at Holyrood Abbey in 1161. Fergus’ great grandson Alan died in 1234, when the Annals of Ulster described him as ‘ri Gallghadil‘- king of the foreign, that is Viking, Gaels- the people who gave their name to Galloway. Alexander II, king of Scots promptly invaded the former kingdom and divided it between the husbands of Alan’s three daughters.

Alan’s youngest daughter was Devorgilla and her husband was John Balliol. His family had lands in the north east of England but were originally from Ballieul in Normandy. As Devorgilla’s sisters and their husbands died off, she and her husband re-assembled the lordship of Galloway. Under different circumstances it is likely that Galloway’s distinctiveness would have slowly faded away as the heads of the region’s Gaelic speaking kindreds (clan chiefs) became feudal tenants of their Balliol lords.

Instead, the wars of Scottish independence revived Galloway’s distinctiveness. The region’s support for the Balliols placed it ultimately on the losing side of a civil war which ran in parallel with the ‘Great Patriotic War’ waged by the Bruces and their supporters against English kings Edward I, II and III. It is important to remember that despite King Robert I victory at Bannockburn in 1314, Galloway remained hostile territory for the Scots.

To control Galloway, King Robert first made his brother Edward Lord of Galloway in 1309 and then set about planting Bruce supporters in lands across there region. This included granting the barony of Buittle to James Douglas in 1324- including Buittle castle, the Balliol’s chief residence.

These new Scots speaking land owners then lost their Galloway lands when Edward Balliol was in power. Balliol had to rely on Gaelic kindreds like the McDowalls and McCullochs to support him in Galloway. This strengthened the power and influence of Galloway’s Gaelic population.

Even after Edward Balliol gave up his claim to the throne in 1356, David II had difficulty re-establishing control over Galloway. After Balliol’s death in 1365 he came up with a plan to gift Galloway to Edward III’s son John of Gaunt. The plan was rejected, but Archibald ‘the Grim’ Douglas was at the meeting.

It may have been David’s plan to get rid of Galloway which gave Archibald the idea of making himself Lord of Galloway. David granted him eastern Galloway (between the Nith and the Cree) in 1369 and then, after David’s death in 1371, bought western Galloway (Wigtownshire) from the Earl of Wigtown for £400 sterling in 1372. The new/ revived Lordship of Galloway lasted until 1455 when it was forfeited to James II by James, 9th earl of Douglas and the last Lord of Galloway.

Although the administrative language of the Douglas lordship of Galloway was Scots, it preserved the territorial integrity of Galloway. The Douglas lords preserved Galloway’s traditional laws and kept direct Scots influence at bay. This helped to preserve Galloway’s Gaelic language and culture, but as an enclave isolated within the now Scots speaking lowlands.

Were the exploits of Galloway’s Gaelic kings and lords celebrated in poetry and song? Unfortunately although Òran Bagraidh (A Song of Defiance) mentions some Galloway and Ayrshire family names-

Muinntir na Dubach’s -Kindred of the black feet -Kennedies

Sliochd na feannaig -Tribe of the crow - Craufurds?

Cinneil sliochd a‘ mhaduidh -Tribe of the wolf or dog - MacLellans

Sluagh na gruaigi ciar - Tribe of the dusky hair - Douglases?

- it probably refers to an event which took place in 1527, the murder of Gilbert Kennedy, earl of Cassillis by Craufurd of Kerse. [Several Craufurds were involved, but the instigator was Hugh Campbell, sheriff of Ayr].

As I have discussed previously, although several folktales from Galloway mention Robert the Bruce, they can only be traced back to the beginning of the nineteenth century. None of them are mentioned by Andrew Symson in his late seventeenth century ‘Large Description of Galloway’. Symson does mention an ancient monument believed to be the grave of King Galdus, but I have found that Galdus was the invention of historian Hector Boece in 1527.

Symson provides a very useful and detailed description of Galloway as it was in the 1680s, but it is a Galloway without any history. There are no tales of ‘good King Fergus’, no accounts of how Gille Brigte had his brother Uhtred gruesomely killed nor of Lord Alan. Even the romantic origin of Sweetheart Abbey although the foundation of Whithorn by St Ninian is mentioned. The next 1000 years of Galloway’s history are passed over in silence until the execution of Patrick McLellan by ‘the Black Douglas’ at Threave castle in 1452. Symson also notes ‘the common report in the countrey’ that Mons Meg (by then in Edinburgh castle) was constructed on Threave island. Both these stories, or variations on them, were still circulating locally in the eighteenth century and remain part of Galloway’s folk history.

Symson’s study was not published until 1823, when the historical details lacking in Sysmon’s original text were filled in by a series of extensive footnotes.

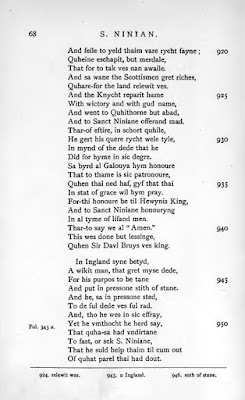

There is one near contemporary account of an event in Galloway. Part of a long poem in Scots written circa 1400 about the legends of St Ninian describes how Fergus McDowell was saved from an English raiding party by the intervention of St Ninian in a dream. The poem mentions McDowell’s ‘menstrale, Jak Trumpoure’. In 1365, David II confirmed Dougal McDowall’s grant of ‘Littilgretby’ (now Gribdae farm) to John Trumpoure who is described as a herald.

Fergus and Dougal McDowall were brothers. They were the sons of Duncan McDowall who had been, like his father Dougal, Balliol supporters. Duncan swapped sides between the Balliols and the Bruces several times between 1332 and 1356. But by 1365 McDowalls were reconciled to the Bruces and therefore no longer allies of the English.

The McDowalls were one of the most important of Galloway’s Gaelic kindreds. The last reference to a McDowall as ’head of kin’ is from 1474. However, the ebb and flow of the civil war in Galloway in the 1340s had led to the capture of Duncan McDowall by the English. Along with his wife and sons, he was kept in the Tower of London until he agreed to re-enter the fray on the side of Edward Balliol again. To ensure he did not swap sides again, his wife and sons had to remain in England.

If Duncan McDowall and his sons had only been able to speak Gaelic there would have been communication problems with their English captors. With Edward Balliol having to rely so heavily on the support of Edward III, his leading supporters in Galloway would have needed to be bilingual in Scots and Gaelic. Patrick McCulloch, for example, followed Balliol into exile in England in 1356 and remained there until Balliol’s death in 1364.

In other words, even before Scots speaking Archibald the Grim became Lord of Galloway, while the Bruce/Balliol civil war had strengthened the importance of Galloway’s Gaelic kindreds, the heads of the kindreds would have required a good grasp of Scots and English as well as their native Gaelic.

It is unclear how long Duncan McDowall’s sons stayed in England. The significant point is that the use of Scots to recount the adventures of Fergus McDowall in the Legend of St Ninian is not anachronistic. Fergus and Dougal McDowall would have been Scots speakers, although they would still have needed Gaelic to converse with the majority of their fellow Gallovidians.

Another effect of the Wars of Independence was the strengthening of Scottish identity. Scots was also the language of patriotic epics like Barbour’s ‘Brus’ and (later) Blind Harry’s ‘Wallace’. The tale of Fergus McDowall and his victory over the English fits into this framework. This may explain the survival of the story.

If similar tales from before the 1360s existed, they would not have fitted into a patriotic Scottish narrative. They may well have recounted victories against the Bruces and the Scots. Older poems and songs would have been composed in Gaelic, and may have supported a Gallovidian identity.

To the extent that a combination of shared history, geography, language and culture marked out and distinguished ‘Galloway’ from ‘Scotland’ it would have been difficult for the people of Galloway to recognise themselves in the Scottish identity which emerged from the Wars of Independence.

For Galloway to become Scottish, much would have to be given up. Galloway’s Gaelic language provided a living link with the region’s distinctive past. It also set the region’s people apart from their neighbours in lowland Scotland. After 1455, when even the Douglas lordship of Galloway was extinguished, the assimilation of Galloway into Scotland stepped up a gear. By 1490 the last remnants of Galloway’s traditional laws were abolished by the Scottish parliament. Records of landownership become more comprehensive from the later fifteenth century onwards as Peter McKerlie’s five volume ‘History of the Lands and their Owners in Galloway’ shows.

But although historical documents provide a clearer picture of Galloway after 1455, the effect of what must have been a major cultural shift - the loss of Galloway’s Gaelic language and culture- is invisible. It is not until the seventeenth century that Galloway re-emerges as a region with a distinctive culture again, that of Calvinist Presbyterianism.

This religious culture was not exclusive to Galloway but it was deep rooted. When Charles II attempted to re-impose Episcopalianism after his restoration, every parish minister in Galloway refused to accept. As a result, in 1663, every parish had a new minister imposed. The people rejected the new ministers and flocked to hear their old ministers preach, at first in private houses and then at open air conventicles- which were promptly banned. The reformation had grow deep roots in Galloway.

According to tradition, the first stirrings of the reformation in Galloway began in the Glenkens in the 1520s. Here Alexander Gordon of Airds in Kells parish read from an English translation of the Bible to his family, servants and neighbours in the woods on his estate. Possession of such a Bible was illegal, so these readings resembled the later conventicles. This suggests there may have been later elaboration of the story.

More certainly, analysis of the first Protestant ministers in Galloway shows that 60% had made the transition from the unreformed church. The shift in religion was marked by an important change of language. Church services were no longer conducted in Latin but in Scots and ’Bible English’. In areas of Scotland where Gaelic remained the language of the people, this created problems for the reformers. In 1567 this led to the printing of a translation into Gaelic of ’The Book of Common Order’ by John Carswell. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%A9on_Carsuel

If Gaelic was still widely spoken in Galloway in 1560, this would have hindered the progress of the reformation. However, there are no reports that John Knox or any of the other reformers had problems communicating their message in the region. This contrasts with the reformers anger at the survival of Catholicism in parts of the region. As late as 1605, Gilbert Brown, the last abbot of New Abbey, was still celebrating mass with the support of the local population.

One hundred years later, the Church of Scotland discovered that there were still over 400 Roman Catholics in the eastern parts of Galloway. The survival of the old religion was mainly due to the influence of the Maxwell earls of Nithsdale who were powerful enough to defy the Reformed church.

The Maxwells were not a Galloway family, but had been granted Caerlaverock in Dumfriesshire by Alexander II in 1220. In the 1330s, Eustace Maxwell was a Balliol supporter and Edward Balliol place him charge of eastern Galloway while Duncan McDowall had charge of western Galloway. With Maxwells then, there is a continuity of power and influence stretching back to the time when Gaelic was the language of Galloway and Nithsdale.

If the Maxwells were able to resist even such a major cultural change as the Reformation, this offers the tantalising possibility that, if they had been one of Galloway’s Gaelic kindreds, their influence might have preserved the language as well as their faith into the eighteenth century by supporting Gaelic poets as well as Jesuit priests.

To end on a further speculative note, can the advance of the Reformation in Galloway be linked to the retreat of Gaelic?

As we have seen, the Wars of Independence had the effect of separating Galloway off from the main current of Scottish identity. The creation of the Douglas lordship of Galloway preserved aspects of this separate identity, including Galloway’s traditional laws and the survival of several of Galloway’s Gaelic kindreds, including the McDowalls, McCullochs and McLellans.

How strongly Gaelic survived in Galloway during the Douglas lordship is difficult to establish, but it is likely that Scots was gradually gaining ascendancy. The end of the Douglas lordship would have intensified pressure on Gaelic. Would the loss of Gaelic have been experienced by the Gallovidians as a loss of identity? How difficult would it have been for them to take on a new identity as Scots, along with a new language?

That the entire history of Gaelic Galloway appears to have vanished from the region’s collective memory suggests it was a traumatic change. Yet the folklore and folk history of Gaelic Galloway disappeared to be replaced by Scots folklore and Scots history, including stories of Robert the Bruce, but not Edward Balliol nor any of Galloway’s once powerful Gaelic rulers.

Perhaps Galloway’s embrace of the Reformation in the fifteenth century and the region’s commitment to the Covenanting cause in the seventeenth century have their roots in the adoption of a new, religious, identity as a substitute for what had been lost.

This possibility will be the subject of a later blog post,