Practical Idealism: the Common Weal and Civil Society

Common Weal- Practical Idealism for Scotland.

On 30 July 1971 Jimmy Reid, chair of the shop stewards committee at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders held a press conference where he announced

This is the first campaign of its kind in Trade unionism. We are not going on strike. We are not even having a sit-in strike. We are taking over the yards because we refuse to accept that faceless men can make these

decisions. We are not strikers. We are responsible people and we will conduct ourselves with dignity and discipline. We want to work.

Over the next decade, the UCS occupation was followed by more than 260 worker occupations across the UK. [Alan Tuckman ‘Workers’ Control and the Politics of Factory Occupation’, Haymarket Books, 2011] As well as these occupations, in 1974 the Lucas Aerospace Shop Stewards Combine Committee began working on an alternative Corporate Plan designed to save 3600 jobs threatened by re-organisation. The alternative plan was for Lucas to move out of the military market and begin producing social useful products including kidney dialysis machines, electric cars and wind turbines.

The potential for a radical shift in manufacturing industry from a focus on the pursuit of profit to production for a sustainable future was set out by Victor Papanek in his 1971 book ‘ Design for the Real World-Human Ecology and Social Change’, by David Dickson in 1974 with ‘Alternative Technology and the Politics of Technical Change’ and by Godfrey Boyle and Peter Harper in 1976 with ‘Radical Technology’. As ‘Practical Idealism’ puts it [p.119]

Design and innovation are at the forefront of our hopes for the future. A new generation of designers of all sorts is challenging the old order. Do products have to be mass-manufactured in sweat shops? Do the goods in our houses have to harm the environment in which we live? Must things be designed to wear out? Can’t our communities be planned with good spaces to play in?

Reading through ‘Practical Idealism’, the proposals set out seem eminently sensible and reasonable. The contrast is between an economy based on ‘social provisioning’ and an economy based on ‘social extraction’. Social provisioning is described as ‘the process for taking resources (raw materials and skills) and turning them into things that people need and distributing them to people that need them. Social extraction is ‘the process of taking out of society as much wealth as possible in the shortest time possible with the least investment possible.’ [p.38]

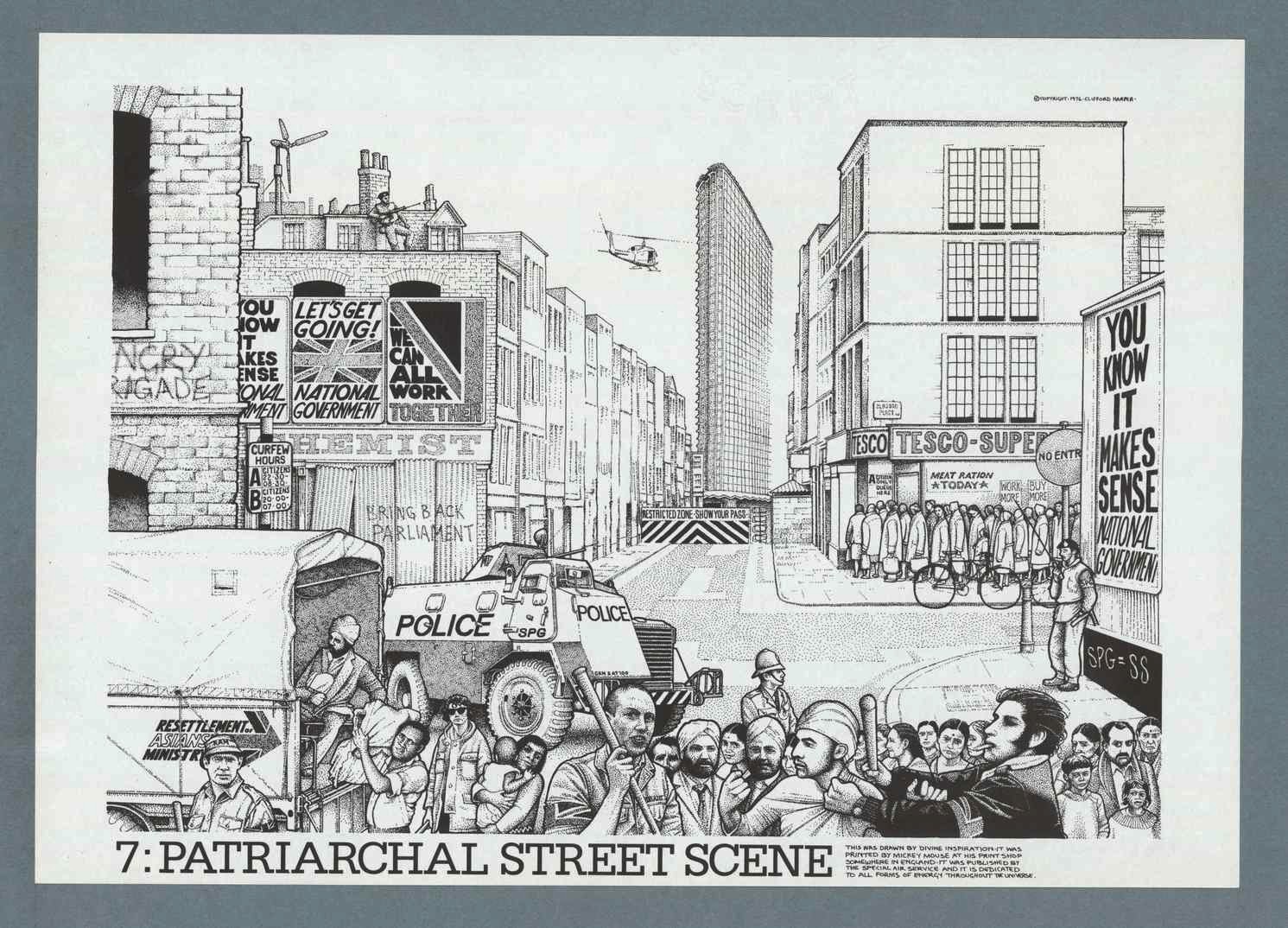

Back in the early 1970s it seemed that social provisioning was the future and social extraction was the past. But then, with election of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the USA, social extraction gained the upper hand in what David Harvey has called the neoliberal counter-revolution. This counter-revolution saw the end of the post-world war two social democratic consensus, when the gap between rich and poor had begun to narrow. Since 1980, the gap has once more widened, returning us to the extremes of wealth and poverty which marked the early stages of the industrial revolution.

In the heyday of the UK as a world power, the process of social extraction was matched by the physical extraction of coal, the fossil fuel which powered the industrial revolution. The fear that Britain’s coal reserves might run out was tackled Stanley Jevons in 1865in ‘The Coal Question’. In his conclusion, Jevons argued against attempts to conserve Britain’s coal reserves for the future.

The alternatives before us are simple. Our empire and race already comprise one-fifth of the world‘s population; and by our plantation of new States, by our guardianship of the seas, by our penetrating commerce, by our just laws and firm constitution, and above all by the dissemination of our new arts, we stimulate the progress of mankind in a degree not to be measured. If we lavishly and boldly push forward in the creation of our riches, both material and intellectual, it is hard to over-estimate the pitch of beneficial influence to which we may attain in the present. But the maintenance of such a position is physically impossible. We have to make the momentous choice between brief but true greatness and longer continued mediocrity.

UK coal production peaked at 292 million tons in 1913, the same year that shipbuilding on the Clyde peaked when 756 973 tons of ships were launched. The eclipse of Britain as a great power since 1913 should have led to the reform and re-invention of the UK as a medium if not mediocre nation. The immense wealth which began flowing from the North Sea oil reserves in the 1970s could have been re-invested in the UK’s infrastructure and in the renewal of our manufacturing industries.

Instead the wealth was wasted in a futile attempt to restore Britain’s greatness by reversing progress towards social provisioning through a return to an economy based social extraction. The answer to the ‘oil question‘ was the same as Stanley Jevons answer to the coal question- maximise extraction now.

The Prologue to ‘Practical Idealism’ states that ‘This is not meant to be a case for or a case against independence but only a case for a better Scotland’ [Prologue p.4] but it is very difficult to see how a better Scotland can emerge as part of a united kingdom which is still haunted by the spectre of Stanley Jevons’ vision of ‘true greatness’. For a better Scotland to emerge, civil society must become self-aware, become conscious of itself- of ourselves. ‘Practical Idealism for Scotland’ is a significant step-forward in this process.

Why is it significant? To understand why we need to go back to an unintended consequence of the Union of 1707- the Scottish Enlightenment. The Union of 1707 created an anomaly which separated political power, now concentrated in London, from Scotland’s intellectual resources - its universities, its Church and its legal establishment. In a development of world historical importance, the Scottish Enlightenment emerged out of this new situation, contributing major advances to philosophy, to political, economic and social theory, to aesthetics and to scientific and technological knowledge.

While Scottish Enlightenment thinkers were keen to distance themselves from the religious ‘enthusiasm’ of the seventeenth century and from Scotland’s medieval past, the idea of civil society developed by Adam Ferguson and Adam Smith contained elements drawn from pre-Union Scotland. Civil society was held to exist between the private realm of individuals and families and the political realm of the government and the state. Civil society was also the realm of economic activity. From this developed the later liberal and current neoliberal belief that government and the state should not interfere in economic activity.

Translated into French and German, the ideas of the Scots thinkers became part of a European wide enlightenment and also influenced political thought in what was to become the United States of America. However, the French Revolution led to a reaction against the more radical aspects of the Scottish Enlightenment. So when Robert Burns composed ‘Scots Wha Hae’ in August 1793 during the trial in Edinburgh of Thomas Muir and William Palmer for sedition as supporters of the French Revolution, Burns had to hide ‘the glowing ideas of some other struggles of the same nature, not quite so ancient’ within a song about the Battle of Bannockburn. Muir was sentenced to transportation for 14 years and Palmer for seven.

While Burns was a radical poet, Professor Dugald Stewart was a leading light of the Scottish Enlightenment. But in 1794, William Craig, a senior judge and Lord of Session, wrote to Stewart asking him to retract a section of ‘Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind’ which Craig believed might ‘unhinge established institutions’. Stewart refused to do so and denied that he was encouraging revolution.

Although the more radical ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment were muted in the nineteenth century, the combination of James Watt’s steam engine and Adam Smith’s doctrine of free trade transformed Britain into the world’s first industrial nation.

In 1818, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars but before the industrial revolution had taken root in Germany, Georg Hegel was appointed Professor of Philosophy at Berlin University in Prussia. Hegel was deeply influenced by Scottish Enlightenment thought, including James Steuart and Adam Smith’s theories of political economy as well as the idea of civil society. However, in Hegel’s version, civil society emerged out the disintegration of the family as the focus of ethical life and in turn a rational state would emerge out of civil society as the ‘actuality of the ethical idea’. The ethical aspect of the rational state would limit the destructive extremes of wealth and poverty found in a civil society based on economic self-interest.

In an essay on the English (British) Reform Bill of 1831, Hegel argued that the minimal reforms contained in the bill would still leave most of the archaic elements of Britain’s constitution in place. Landowning aristocrats would still dominate a minimal (‘external’) state. This in turn might lead opponents of the status quo to inaugurate not reform but revolution. Hegel died in November 1831. Had he lived he might have developed his political theories to include an active role for the organised industrial working class in the movement from civil society to the rational state. Instead it was left to Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx to adjust Hegel’s political theories to include the proletariat.

Since the 1832 Reform Act and further constitutional reforms which extended the electoral franchise, the British revolution Hegel, Engels and Marx all anticipated has been avoided. Under pressure from an increasingly organised working class, the British state began to become more rational. But since the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, narrow economic interested centred on the City of London have ‘re-captured’ the state. Gradually these economic interests have managed to reverse the social democratic policies pursued first by the Liberal party and then by Labour and Conservative governments during the post-war consensus period. In Scotland the response to the Thatcher era was a revival of the idea of civil society. It was pressure from Scotland’s civil society which led to the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999.

In this movement, the active involvement of civil society in the Yes campaign has the potential to create a rational state based on a written constitution as the actuality of the ethical idea. If this occurs it would truly be, in Hegel’s language ‘a world historical event’. However, before this can happen, civil society in Scotland must first overcome -negate- the negativity of the No campaign. To do this civil society must become self-aware, become conscious of its limitations and contradictions and find the will to re-invent itself. Common Weal’s ‘Practical Idealism’ is an essential part of this process.

At the same time, the Radical Independence Campaign have been pursuing a strategy recommended by James Foley and Pete Ramand in ‘Yes-The Radical Case for Scottish Independence’ [Pluto books, 2014]. This strategy involves actively canvassing areas of high social deprivation where voter registration and participation are low. Voters in these areas have become increasingly alienated from the Labour party as it has become part of the neoliberal consensus. By accepting what Mark Fisher calls ‘capitalist realism’ in the 1970s-that there is no alternative to the re-establishment of the conditions for capital accumulation and the restoration to power of economic elites- the Labour party has become part of the problem rather than the solution.

For the Yes campaign to win in September 2014, the majority of current and former Labour voting Scots will have to be persuaded that an independent Scotland offers the best chance of achieving their aspirations for a more rational (post-neoliberal) state. But a yes vote on 18 September will mark the beginning not the end of the real struggle to secure Scotland’s future. As Foley and Ramand ask, will Scotland’s elites ‘freely surrender their existing privileges’? Without coercion, will they submit to the ‘common good’? [p. 64]

In Hegel’s model, Scotland’s elites would be compelled to surrender their privileges as part of the process through which civil society, as economic society, gives way to the rational state. The ethical idea of the rational state is that economic activity must benefit all of its citizens, not just an elite. A state in which only a few benefit from economic activity would not be a rational state.

Unfortunately, such absolute idealism runs smack up against capitalist realism. Under capitalist realism a rational state which attempts to minimise the extremes of wealth and poverty is an impossible state. Under capitalist realism, the state does not exist to secure the welfare of all its citizens. It exists to maintain the conditions for capital accumulation and the power of economic elites. But what Hegel argued 200 years ago, looking at the USA and the UK was that they were forms of civil society, not states. That capitalist realism - and the No campaign- cannot imagine the possibility of anything beyond civil society does not mean that a rational Scottish state is impossible. It just reveals their collective poverty of imagination.

To conclude.

Although the Scottish Enlightenment was the product of an intellectual elite, it was an elite alienated by the Union of 1707 from the new centre of political power in London. This distancing led the Scottish Enlightenment to two related modern concepts- civil society and political economy. Conservative reaction to the French Revolution cut short further evolution of these ideas in Scotland and the rest of the UK. In Germany they were developed by Hegel who argued that the limitations and contradictions of a civil society focused on economic self-interest justified by political economy would give rise through reform to a rational state.

Reflecting on the apparent inability of the UK to properly reform itself and become a rational state, Hegel evoked the spectre of a British Revolution. Engels and Marx added a new element to Hegel’s notion of civil society - a revolutionary class struggle. The crisis of capitalism which began in 2008 and the policies of austerity pursued by the UK coalition government have revealed the limits of civil society and of devolution- without provoking a British Revolution. Instead, with the movement towards Scottish independence, a dramatic solution to the constitutional contradictions of Britain identified by Hegel in 1831 is underway. This revolutionary reform will cut the constitutional Gordian knot by dissolving the Union of 1707.

In this movement, the active involvement of civil society in the Yes campaign has the potential to create a rational state based on a written constitution as the actuality of the ethical idea. If this occurs it would truly be, in Hegel’s language ‘a world historical event’. However, before this can happen, civil society in Scotland must first overcome -negate- the negativity of the No campaign. To do this civil society must become self-aware, become conscious of its limitations and contradictions and find the will to re-invent itself.

Significantly, there parallels between this process and the Marxist concept of ‘class-consciousness’. The Radical Independence Campaign’s contribution to the Yes campaign is an ongoing attempt to re-engage Scotland’s working class communities with the political process, a process which can be described as ‘consciousness-raising’.

Common Weal is not directly engaged with the Yes campaign, arguing that their proposals ‘[are] not meant to be a case for or a case against independence but only a case for a better Scotland’. Common Weal’s proposals have their roots in the progressive ideals of the 1970s, in the movements for industrial democracy, socially useful production and what was to become the Green movement. These movements had the potential to deepen and extend the social democratic post-war consensus but were blocked and then suppressed by the neoliberal counter-revolution.

Shared by both Common Weal and the Radical Independence Campaign is a focus on the recent past which has been dominated by the neoliberal counter-revolution. However, since, neoliberalism has its roots in Scottish Enlightenment theories of political economy and civil society, we should be aware that our debates and discussions about Scotland’s future are also haunted by the ghosts of Hegel and Marx.