Coal as Capital

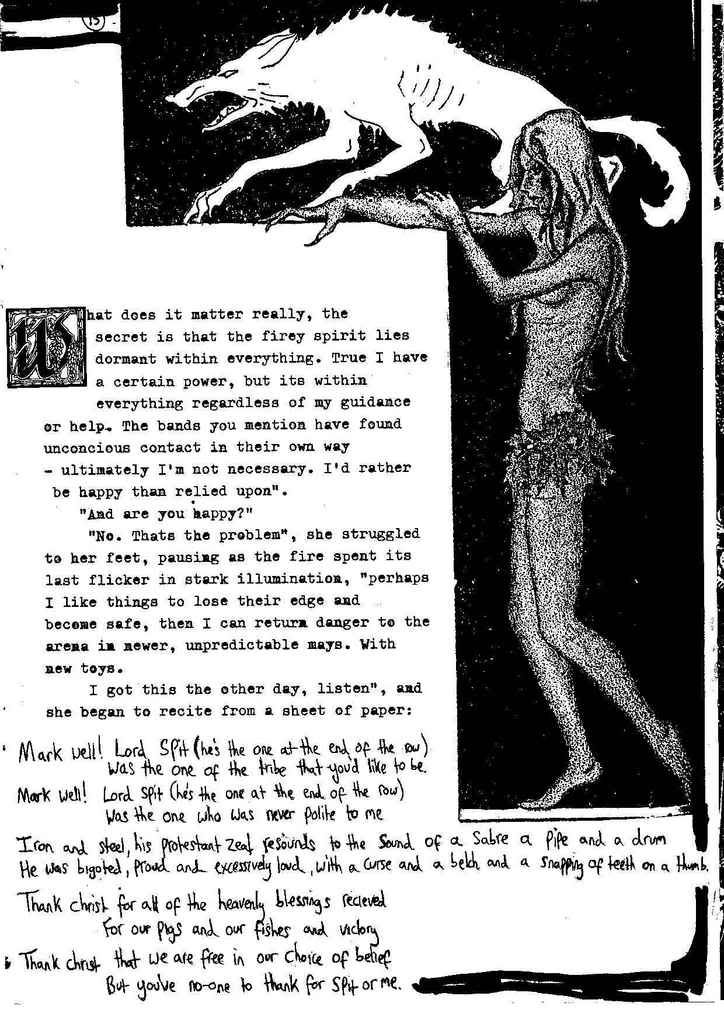

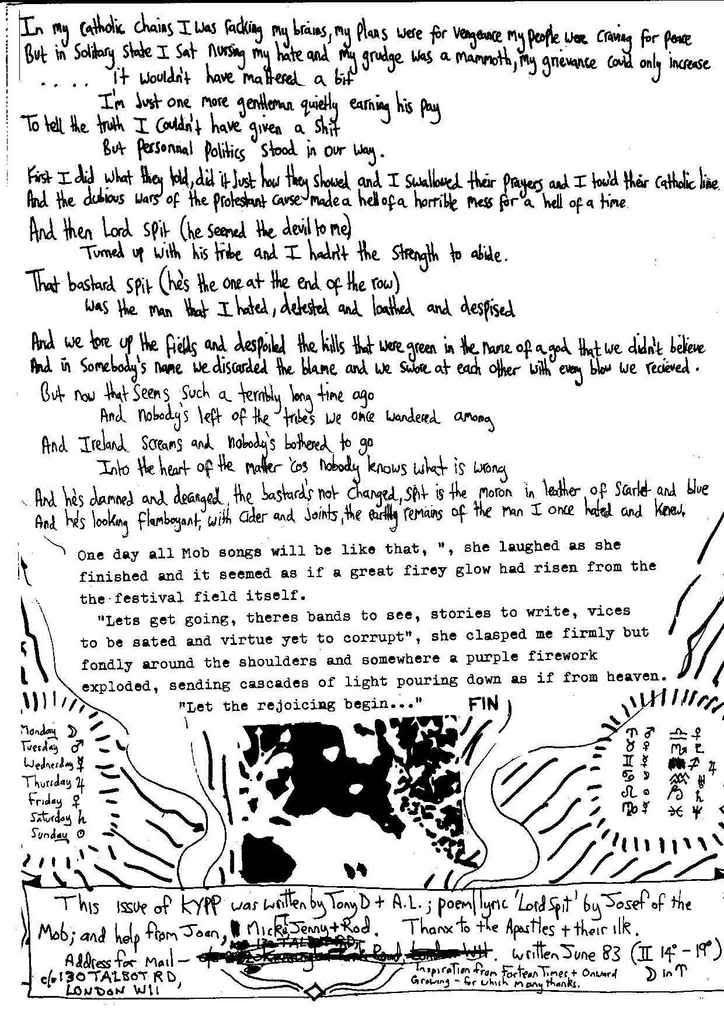

|

| NCB tank engine near Dalmellington 1960s |

No coal? No capitalism! Discuss.

Inspired by this book of photos of Ayrshire mines and miners-

Mining: Ayrshire’s Lost Industry- Guthrie Hutton, Stenlake Publishing, 1996

I was brought up in a house beside a railway to the small town and port of Kirkcudbright 10 miles away. The railway passed underneath a road which led to the much larger town and port of Ayr 50 miles away. Before it closed in 1965, I travelled by steam train to Kirkcudbright a couple of times. After it was closed, I missed seeing and hearing the steam trains, but for another ten years or so the road to Ayr offered a glimpse of steam in action around the coal mines at Dalmellington.

The Ayr road (A 713) winds its way up through the green valley/ glen of the rivers Dee, Ken and Deuch which are part of a hydro-electric scheme built in the 1930s. Beyond Dalry the road climbs up onto a mix of moorland and forestry and the tiny village of Carsphairn between by the Rhinns of Kells and Cairnsmore of Carsphairn which are 2500 feet high hill ranges. Beyond Carsphairn the road crosses the watershed between rivers flowing south and rivers flowing north. It then enters a narrow rocky ravine, winding and twisting beside the Muck Water as it drops down towards Dalmellington. From Dalmellington down to Ayr, the road was joined by a railway, originally planned in the 1840s to carry on past Dalmellington down through Galloway to the Solway Firth at Balcary Bay near Auchencairn. Back in 1803, a canal following a similar route had been planned to give Galloway access to the coal already being mined around Dalmellington - since despite several efforts, no coal had been found (since it did not exist) in Galloway.

|

| Rhinns of Kells from Carsphairn |

Since there was also iron ore in the hills around Dalmellington, the Dalmellington Iron Company was set up in 1847- but had to wait until 1856 for the railway to reach the town and the link on to Galloway was never built. The iron works lasted until the 1920s, but the associated coal mines survived until 1978 and open cast coal mining continues in the area. The many coal mines in the area around Dalmellington still used small industrial steam engines to haul the coal down to the docks at Ayr - where most of it was exported to northern Ireland. The railway is still open, but nowadays the open cast coal is hauled out by diesel-electric engines.

Back in the late sixties/ early seventies, when the steam engines, the mines and the huge ‘bing’ (a large mound of waste from the iron works and coal mines) at Waterside were still part of the landscape, the contrast between rural Galloway and industrial Ayrshire was very dramatic and powerful. In the course of a few miles a shift from a still essentially eighteenth century (despite the hydro-electric dams and power stations) to the nineteenth century occurred. Between Carsphairn and Dalmellington, the industrial revolution suddenly happened. There was also, although I didn’t realise at the time, a political and cultural shift from Conservative voting Galloway to Labour voting Ayrshire.

|

| Beoch drift mine, opened 1936, closed 1968. North-east of Dalmellington, at 1068 feet, was highest coal mine in Scotland. |

Thinking about it now, if coal had been found in Galloway, would this have lessened the economic, political and cultural difference between Ayrshire and Galloway? Probably it would. I now know that a small group of young men from the Glenkens (on the non-coal side of the geological divide) moved to north-west England in the late eighteenth century as apprentices to a machine maker (who also came from the same area) and went on to found the two biggest cotton spinning businesses in Manchester. [Kennedy and McConell and A and G Murray]. They were amongst the first to successfully use steam power to spin cotton and one (John Kennedy of Knocknalling and Ancoats) was closely involved in the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first ‘inter-city’ railway. [Older railway were built to link coal mines with ports].

The growth of the Manchester cotton industry as an ’industrial revolution’ was observed at first hand by Friedrich Engels in 1842/3. These observations influenced both Engels and Karl Marx.

The Proletariat originated in the industrial revolution, which took place in England in the last half of the last (18th) century, and which has since then been repeated in all the civilized countries of the world. This industrial revolution was precipitated by the discovery of the steam engine, various spinning machines, the mechanical loom, and a whole series of other mechanical devices. These machines, which were very expensive and hence could be bought only by big capitalists, altered the whole mode of production and displaced the former workers, because the machines turned out cheaper and better commodities than the workers could produce with their inefficient spinning wheels and handlooms. The machines delivered industry wholly into the hands of the big capitalists and rendered entirely worthless the meagre property of the workers (tools, looms, etc.). The result was that the capitalists soon had everything in their hands and nothing remained to the workers. This marked the introduction of the factory system into the textile industry. [Freidrich Engels, 1847, The Principles of Communism ]

However, missing from Marx and Engels’ critiques of political economy was an understanding of the ‘thermodynamics of capitalism’. The science of thermodynamics developed in the nineteenth century as attempts were made to better understand the scientific principles of steam (heat) engines. The practical improvement of steam engines from Newcomen’s 1712 atmospheric engine through the Watt engine to Trevithick’s high-pressure steam engine were based on technological/ engineering trial and error rather than abstract science.

Marx and Engels concentrated on the concrete - human labour; rather than the abstract - fossilised energy; in their attempts to understand the dynamics of capitalism. But, as Tony Wrigley argues in ‘Energy and the English Industrial Revolution’ [ Cambridge, 2011] without coal there would have been no industrial revolution. And so no proletariat.

The problem is growth. As David Harvey [The Enigma of Capital, 2010] explains it, capitalism depends on economic growth, on a cycle through which the capital invested at the beginning of the productive cycle has increased by the end of the productive cycle. Labour, human work, is essential to this process, adding value to the capital invested since only part of the value added is returned to labour (the workers) via wages. Most of the value added is creamed off as ‘profit’, which is then re-invested to start the cycle working again. Without growth, without economic expansion, the system would not work.. Without coal, the ability to expand and grow would have been limited by a whole set of natural limitations. Huge forests would have been needed to provide timber for fuel while at the same time huge amounts of land would have been needed to grow fodder for horse transport and food for the industrial work force. Coal replaced wood as fuel (including iron smelting) and was the energy source for the steam engines which increased the speed of production and distribution. Coal was the fuel which powered the unlimited expansion of capital.

|

| Late eighteenth century English coal mine. |

Working forward from the history of the Galloway Levellers uprising of 1724 to the later eighteenth century improvement of agriculture in Galloway, I found it went hand in hand with attempts to create a cotton industry in Galloway - as a way to provide employment for the people cleared off the land by improvement. The local cotton factories were water powered and lost out to Manchester‘s steam powered cotton mills. So Galloway remained a rural/ farming economy and society. But , as I discovered, a group of young men (teenagers) who left Galloway to become apprentices near Manchester were able [see above] to become leading cotton spinning factory owners in Manchester.

Then, a few days ago, I found Guthrie Hutton’s book on the coal mining industry in Ayrshire. There is not much text, it is mainly 200 or so photographs from the 1880s to the 1960s. The photographs are of the mines (above and below ground), the miners and the ‘rows’ they lived in. Some are of the mines I remember seeing forty years ago. Looking through the book has been a revelation, has shifted my perception and understanding of ‘local’ history in the same way that discovering the links to Manchester did.

Realistically, the cotton industry could never have taken off in Galloway, could never have transformed its towns and villages into industrial cities. But if coal had been found beneath the fields and moors of Galloway, then Galloway’s development would have been similar to that of Ayrshire. Mines would have been dug, rows of shoddy houses put up for the miners and their families and a network of industrial railways (or canals) built to carry away the coal. The whole culture- social, economic and political - of the region would have been different.

|

| Sorn drift mine, east Aysrhire. Closed 1983. |

So if I ask the question now “What is the history of Galloway?” - my answer is “An accident of geology.”

Could capitalism be the product of a similar ‘accident of geology’? If the British coal fields had been buried just a bit deeper, the early shallow coal mines could not have been developed so the early industrial revolution would not have been able to take-off in places like Manchester. Without shallow mined coal from Newcastle, London could not have grown so large in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Without the demand for coal, the need to push mines deeper would not have existed and so Newcomen’s atmospheric steam engine would not have been needed…so James Watt would not have developed his improved engine…

The counter argument is that the culture of scientific knowledge and technological improvement fostered by the Enlightenment would have led to such developments anyway. I am not so sure.

The reality of thousands of men, women and children hacking out the coal and hauling it to the surface is not very ‘Enlightened’.

To be continued…