The Festivalization of Punk

The Festivalization of Punk: Punking up the Festivals

|

| 1981-when the Puppy Collective met The Mob |

Margaret Thatcher had just got re-elected on a wave of imperial nostalgia. As dawn broke and the horror hit us, Tony Drayton and myself grabbed a tin of paint and wrote those words on a wall overlooking the North London Railway. A few days later the Kill Your Pet Puppy Collective plus The Mob set off for Stonehenge free festival. I stayed to feed the cats and go to work at London Rubber.

I wrote Encyclopaedia of Ecstasy Volume One then and later some pages for Kill Your Pet Puppy Number Six. It was to be the last KYPP. The Mob played their last (until 2012) gig in November 1983. Fast forward to 24 June 2016 and the results of the EU referendum came through. It was a similar shock, as if the ghost of Margaret Thatcher had risen from the grave...

I started this- third- review of a book 'Festivalized'- before 23 June. It was difficult to finish, the future overshadowing the past. To make a connection between now and then, I have taken an old greengalloway post and interlaced new text between the pages of KYPP 6.

Warning- this book will blow your mind! It is called Festivalized and it is about the music, politics and alternative culture of the free-festival movement. It is 320 pages long but I read it in a day. The day was the 1 June, the 31st anniversary of the Battle of the Beanfield. Two weeks later and the memories and connections the book sparked off are still haunting me.

What makes the book so fascinating is the way it weaves together ‘music, politics and alternative culture’ through 40+ personal accounts to build up a dynamic picture of the free-festival movement. Steve Lake of Zounds is one of the people interviewed for the book. Steve mentions how Zounds met The Mob -‘a punk band who were travelling with Here and Now’- at a free-festival. [Page 108] In August 1981 the Kill Your Pet Puppy collective met up with The Mob at mini free-festival. It was a very creatively fruitful encounter. I remember discussing how to finance what was to become ‘Let the Tribe Increase’ with Mark Wilson in the kitchen of Puppy Mansions in 1982 and in 1983 the theme of KYPP 6 was a Mob inspired journey to Stonehenge free festival.

This intertwining of punk and the free-festival movement which ‘Festivalized’ documents was touched on but not developed by Jon Savage in his account of punk’s immediate (1975) origins in ’England’s Dreaming’ (1991, pp 111-112).

[Squatting] was a harsher version of the hippie dream, with a sound track by the group Hawkwind, but it was none the less potent. With the dole, squatting made living in central London accessible and affordable. This access allowed the rapid city-transits of the Punk period.

The first free-festivals were held in Windsor Great Park 1972-74, followed by the first Stonehenge festival in 1974. The bizarre state sponsored Watchfield free festival took place in August 1975. The first Sex Pistols gig took place in November 1975. When punk band ATV played at Stonehenge in 1978, there were only about 4000 people there. By 1983 there were about 40 000. It was only in 1976 that there were enough free-festivals for people to travel from one to another rather than returning home in between.

In other words the free-festivals grew and developed in parallel with punk and were in their own way a response and reaction to the recuperation of the 60s cultural revolution by the music business and mainstream media.

The 60s cultural revolution was inspired by acid, H-bombs and automation. Automation was the technology of a future without work where computers and robots would create a world of abundance rather than scarcity. It would be the fulfilment through capitalism of Marx’s vision of a communist society

where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic. [German Ideology, 1845]

Adding acid to the mix immanentized the eschaton [see http://illuminatus.wikia.com/wiki/Immanentizing_the_Eschaton ]

What is to come tomorrow

Let it come today

What is to come today

Let it come right now

Say not, now and then

Oh lord white as jasmine

[Mahadevi]

We want the world

And we want it

We want the world

And we want it…

…Now

[Jim Morrison]

Automation didn’t deliver and the H-bombs never fell. But as the sixties gave way to the seventies the acid inspired visions of UBut thanks to the H-bomb this potential future was at any moment liable to be vapourised. bi Dwyer and Wally Hope (Phil Russell) drove the psychedelic revolution forward into confrontation with the British state.

Dwyer organised three free festivals held in Windsor Great Park between 1972 and 1974. Windsor is a Royal Park, close to Windsor castle#, one of the many official residences of the UK royal; family. Holding a free festival at Windsor, squatting the Queen’s back garden, was a politically symbolic act and the British state responded by violently evicting the psychedelic squatters in 1974.

The first Stonehenge free festival was held in June 1974 but attracted only two or three hundred people. Its location was as symbolic as Windsor, but at a different deeper level. Stonehenge is older than England and its kings and queens. It is older than Glastonbury with its myths of the Holy Grail and which had been attracting mystically inclined hippies since the late 1960s.

In 1978, when ATV, Here and Now and The Mob played, the festival only attracted about 5 or 6000 people. By 1984, the last year it was held, numbers had grown to between 40 and 60 000. If it had continued numbers attending could easily have reached 100 000. For comparison the highest recorded attendance at Glastonbury unfree festival was 153 000 in 2005.

One of the most fascinating things about ‘Festivalized’ is the way the multiple accounts of the participants highlights the crucial difference between unfree festivals like Glastonbury and the free festivals. Unlike unfree festivals, at free festivals the music was only part of what was going on. The main appeal of free festivals was the discovery by those who went that the festivals were not manufactured products to passively consume but collectively constructed situations to be actively experienced.

No doubt the acid helped, but in ‘Senseless Acts of Beauty’ (1996, pp 19-21) George McKay gives an account of his experience of Stonehenge free festival 1984 and how he changed from feeling an alienated outsider to an integrated insider ‘comfortable and at ease’ with the festival. As part of the punk generation, McKay was also struck by the blurring of difference between hippies and punks in the eight years since the year zero of 1976.

What is interesting about Anthony Barnett’s discussion of Englishness and Britishness is that he sees a separation between the two as emerging since 1999 when Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland but not England gained powers devolved from the UK parliament. Many voters in England are annoyed because they feel that England is missing out through not having its own devolved parliament.

But if such a parliament was created, it would diminish the power of the British/ UK parliament and lead to a Disunited Kingdom. Who would be more powerful -the First Minister of an English parliament? Or the Prime Minister of the Westminster/ UK parliament?

To avoid this situation neither Tory nor Labour have supported moves towards setting up an English parliament. Barnett argues that this has led to a displacement of English resentment from a focus on the Westminster parliament onto the EU, which Ukip and anti-EU Tories have exploited.

But if a section of English society were at least uncomfortable and at most outraged by Margaret Thatcher’s Falklands era British/English nationalism, the separation of British from English identity had begun long before devolution in 1999. And one of the first signs of this disaffection is the ’Union Jack with Smiley Face’ flag used by Wally Hope/Phil Russell and the Wallies at Stonehenge in 1974.

While Jamie Reid stuck a defaced queen on the union jack for the Sex Pistols, the Wally flag reduces the flag and all its stands for to inanity. Like watching the Trooping of the Colours or the State Opening of Parliament on acid when the whole monstrous solemnity of the events flips over into a spectacle of side-splitting hilarity, the Wally flag mocks the pretensions of the past.

Even before the Sex Pistols, the alternative culture saw no future in England’s endless imperial dreaming. It dreamt of William Blake’s Albion and of a time at once before and after Empire.

The golden age of the future comes

That which was dreamed of in the past

Where freedom reigns on minds at peace

Minds rich in wisdom to the last

We are the children of the sun

And this is our inheritance

No longer chaos and confusion

But love and laughter, song and dance

[Hawkwind ‘Children of the Sun’, on ‘In Search of Space’, 1971]

That the reality of free festivals, even in the early days, could be chaos, confusion and violence is documented in ‘Festivalized’. But the vision of an alternative England they represented became increasingly attractive as the patriotic frenzy unleashed by the Falklands War sent shock-waves through the fabric of English society.

The economic policies of the Thatcher government had already torn the heart out of manufacturing industry, creating a reserve army of the unemployed which fatally weakened the trade unions and organised labour. What the Falklands War allowed was an intensification of this class war. As the miners were to discover, if the Argentineans were the ‘enemy without’ then they could be classified as the ‘enemy within’.

The revival of the Cold War added to the sense of crisis. Plans to allocate the UK nuclear Cruise missiles saw a rapid rise in CND membership and the establishment of dozens of peace camps at nuclear bases around the country.

The cumulative effect then was to increase the pool of people who were attracted to the Stonehenge free festival as an actually existing alternative to Thatcher’s England. Unlike other free festivals, the Henge, through its proximity to the Stones, was able to tap into a mythical version of Englishness which could be counterpoised to Maggie’s manic vision.

But was it ‘Englishness’? I think so. No equivalent of the Stonehenge festival emerged in Scotland or Wales. It was unique in its size and its connection to a powerful symbol of an ‘England before England’, a deep dreamtine in which all of England’s history could be dissolved and recombined in an endless kaleidoscope of other Englands. Brian Aldiss’ 1969 psychedelic sf novel ‘Barefoot in the Head’ reads like documentary of the time.

Aldiss's story begins in the aftermath of a new World War, during

which bombs filled with hallucinogenics fell on many European cities. Peace now reigns, but social norms and institutions have collapsed as citizens struggle to distinguish between reality and drug-induced fantasy. Building are intact, but the minds of the citizenry have been pharmaceuticalized…

Was the attempt to create an alternative England really a threat to the British state? An inconvenience no doubt, but a threat? Hardly. Yet great efforts were made to stop the Stonehenge festival and break up the related travelling culture.

If there was a threat it lay in the subversive appeal of refusal. A refusal of the neoliberal consensus which has become even more dominant since the Thatcher era. But although the Thatcher era is associated the rise of neoliberalism, there is nothing particularly English about neoliberalism, it is just the latest version of global capitalism. Indeed there is a contradiction in here. Neoliberalism is destructive of historic local (national) identities because they resist the free flow of capital, of commodities and labour. Marx and Engels noted this in 1848.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors”, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.

The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil, and has reduced the family relation to a mere money relation.

It is quite confusing. I have just been reading ‘The Englishness of English Punk: Sex Pistols, Subcultures and Nostalgia’ by Ruth Adams (2008) suggested by Matthew Worley. A quote…

The Pistols, then, might be regarded as unlikely guardians of English Heritage, albeit expressing a history which stressed the popular cultural and the radical dissenting pamphleteering elements of that heritage rather than the more conventional (pro)monarchical and aristocratic aspects.

But there was more to punk than the Pistols and by the time Kill Your Pet Puppy 6 came out the Pistols had been over for five years- although it seemed more like 50 due to the intensity of the Thatcher years.

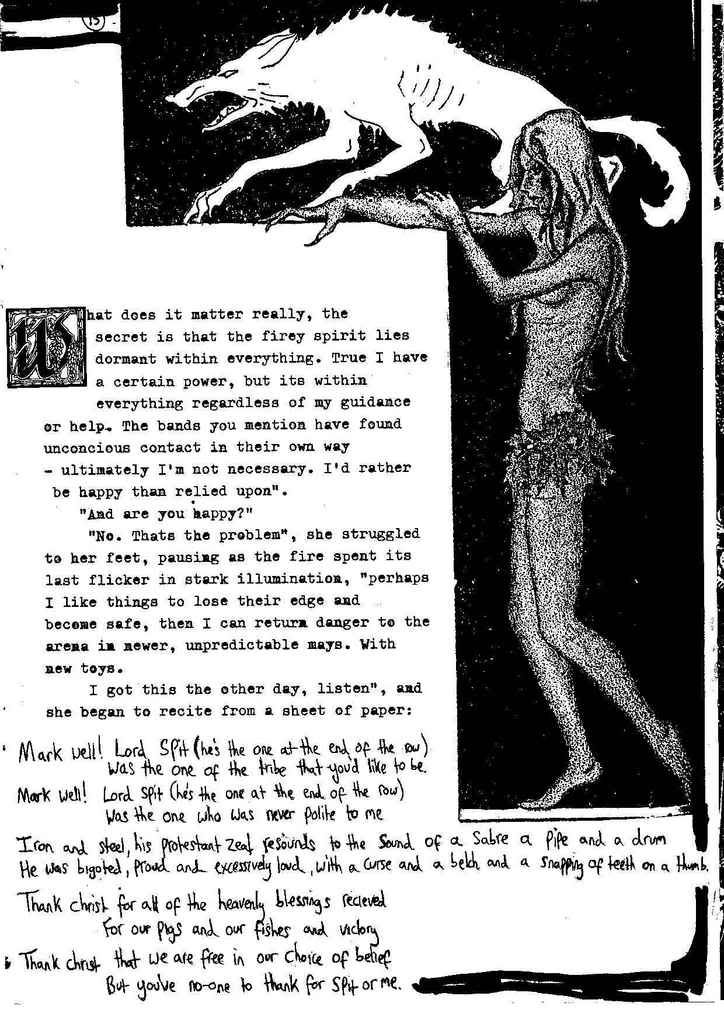

Unlike previous KYPPs or Ripped and Torns before them (R & T started in late 1976), KYPP 6 was a narrative, the story of a journey from the punks squats of London to a free festival at Stonehenge. The shift in perspective was influenced by Mark Wilson and The Mob who -as mentioned above - we met at a micro-free festival on Parliament Hills in August 1981. By 1983 Mark and Josef (ex-Zounds, then drummer with The Mob, later of Blithe Power) were living in the same Black Sheep Housing Co-op as the Puppy Collective.

It is quite confusing. I have just been reading ‘The Englishness of English Punk: Sex Pistols, Subcultures and Nostalgia’ by Ruth Adams (2008) suggested by Matthew Worley. A quote…

The Pistols, then, might be regarded as unlikely guardians of English Heritage, albeit expressing a history which stressed the popular cultural and the radical dissenting pamphleteering elements of that heritage rather than the more conventional (pro)monarchical and aristocratic aspects.

But there was more to punk than the Pistols and by the time Kill Your Pet Puppy 6 came out the Pistols had been over for five years- although it seemed more like 50 due to the intensity of the Thatcher years.

Unlike previous KYPPs or Ripped and Torns before them (R & T started in late 1976), KYPP 6 was a narrative, the story of a journey from the punks squats of London to a free festival at Stonehenge. The shift in perspective was influenced by Mark Wilson and The Mob who -as mentioned above - we met at a micro-free festival on Parliament Hills in August 1981. By 1983 Mark and Josef (ex-Zounds, then drummer with The Mob, later of Blithe Power) were living in the same Black Sheep Housing Co-op as the Puppy Collective.

The Mob had played at Stonehenge in 1978 at later festivals. The Mob connection inspired not just KYPP 6 but actual trips to Stonehenge in 1982, 83 and 84. As ‘Festivalized’ shows, this was part of a wider crossover between punk and the free festivals.

But was this all part of the construction of an alternative Englishness rather an alternative Britishness? I have been living back in Scotland for 19 years and from that perspective, especially from the intense two years of the Scottish independence referendum campaign and its aftermath, it does seem more English than British. If it had been British, then the free-festival/ punk intersection would have had an impact in Scotland. Punk certainly did, but not the later, 1980s, developments. Those developments simply did not register in Scotland and the whole era is unknown. Viewed from Scotland, alternative England as it was and is, is invisible.

But then, even within England, unless you were part of the alternative culture it is also invisible. Instead, reactionary Englishness, the Englishness which saw the Falklands War as a ‘Nazi invasion of Ambridge’, of Nigel Farage and Ukip, of the ‘take our country back’ Leave campaign appears to prevail

If it was easy to define as percentage vote based on the EU referendum, then 53.4 % of England is reactionary and 46.6% of England is radical. Nothing is ever that straightforward though, but on a best guess using social media interactions, alternative England voted remain. Not through love of the EU, but because of the Leave campaign represented precisely that England the alternative culture was an alternative to.

To take England back to a time before the EU is to take the country back to the late sixties /early seventies when the alternative culture emerged and to the intertwined origins of the free festivals and punk in 1974 when the Labour government elected in October promised to hold the first EU (EEC/ Common Market then) referendum…

1974. For future punks it was the year of the Diamond Dogs and for pot-head pixies the year Gong released You. The year of the last Windsor free festival and the first Stonehenge one.

And then here we are now, these words tucked away between the pages of Kill Your Pet Puppy Six, written in 1983, so close to 1984, so far from here in 2016.

Were the words and images, which surround these words and images, part of an alternative England? Of an alternative future? The soundtrack to KYPP 6 is 'Let the Tribe Increase' by The Mob. There is not much escapism in the songs, they are angry and punk as fuck.They are also defiant.We had no illusions about the future, we knew that it was going to be hard. Yet there was also a determination that we would not give up, that we would carry on and continue. That, as George McKay was to put it later, that ours was a culture of resistance.

It was, it still is a culture of hope and celebration. Mob gigs were not gloomy events, they were joyful, colourful, uplifting events. There was a powerful sense of solidarity which has endured. More the 30 years on the friendships and connections made then are still there.

Idealism tempered by realism. Realism inspired by idealism.

Yeah, that sounds about right.

1 Comments:

very detailed report al you must have a good memory...(and archive)!.

Post a Comment

<< Home