Dumfries and Galloway Viking Saga Trail

Vikings

in the landscape and in history.

Map

Key

1.

Kilmorie Cross, Kirkcolm- Viking/ Christian carved cross.

2.

Ruthwell Cross- Anglo-Saxon cross with runic inscription.

3.

Nithsdale Cross- Anglo-Saxon cross and Viking grave nearby.

4.

Whithorn- Irish (Dublin) Viking connection.

5.

Trusty’s Hill- possible Viking/Pictish carved stone.

6.

Threave- Iron Age, Roman, Viking, Viking-Gael, Medieval centre of

power.

7.

Kirkcudbright-Viking grave, Viking Hoard display

8.

Annandale- Anglo-Saxon, Norman, Bruce family castle and lands.

9.

Carrick-Viking-Gael, Bruce family lands

10.

Buittle- Viking-Gael, Balliol family castle and lands.

From

Kirkcolm in the Rhinns to Ruthwell in Annandale, the discovery of

Dumfries and Galloway’s Viking Hoard has opened up a new

perspective on the region’s rich and complex history.

Without

the Vikings, the region may well have remained part of the Kingdom of

Northumbria to be absorbed into Norman England in the eleventh

century- as Annandale and Eskdale nearly were. Alternatively, the

region might have been absorbed into a Dublin dominated Irish Sea

Viking kingdom- as much of Wigtownshire briefly was.

Instead,

by introducing Gaelic speakers to the region, the Vikings helped

create a ‘Greater Galloway’ in the south-west. As this

Viking-Gaelic region was absorbed into Scotland, the descendents of

Fergus of Galloway and Robert de Brus of Annandale became entangled

in a power struggle which lies at the heart of Scotland’s story.

Vikings

in Kirkcudbright

The

presence -in whole or part- of a Viking Hoard in Kirkcudbright will

attract visitors to the town. As well as the hoard, the visitors to

the new art gallery will discover a set of paintings. Many of these

paintings reflect the landscape of Galloway as it was over 100 years

ago.

Over

the past 100 years the landscape has changed. The expansion of

forestry in the uplands and the intensification of dairy farming in

the lowlands have changed the appearance of the landscape as well as

the lives of those who making their living from the land.

Go

back over 1000 years and the difference between the landscape as it

was then and as it is now becomes even greater. Only the boldest

features -the coastline, the rivers and hills- would be familiar. The

farmed landscape, the roads, villages and towns, marshes and even

some lochs, would all have been very different.

However,

dotted here and there across Galloway and Dumfries are a few fixed

points around which the region’s history has revolved.

For

example the Kilmorie Cross at Kirkcolm near Stranraer combines

Christian and Norse mythological elements drawn from the story of

Sigurd the dragon-slayer. It is dated to the tenth century and shows

that Viking settlers in this area of rich fertile soils had become

Christian. It is therefore a near contemporary of the Hoard.

Kilmorie

Cross, Kirkcolm

In

the east of the region at Ruthwell is an older cross, a product of

the Northumbrian church. It also has a fragment of an Old English

poem, ‘The Dream of the Rood’ carved in runes on it. This is of

great historic significance.

Gauin

doun the sides the’r a poyem carved in

runes in the Auld Angles leid. Cryed the ‘Dream

o the Rood’ (rood bein the auld word for

cross) – this is noo the auldest text in

Auld-Angles that we ken belangs Scotland. It is fae this self an same

Auld-Angles tongue that the Scots spoken the day –

in modren Scotland – is sprung. [Centre

for the Scots Leid]

Ruthwell

Cross with runic inscription.

Close

to Thornhill in Nithsdale there is another, later Northumbrian carved

cross. At Carronbridge nearby, a Viking was buried with his sword a

few yards from a Roman road. Was the Viking part of a raiding party?

Possibly, but the sickle he was also buried with suggests a more

settled lifestyle.

Nithsdale

(Thornhill) Anglo-Saxon Cross

At

Whithorn there Northumbrian bishops from Pehthelm in 730 to

(possibly) Heathored in 833. The church at Whithorn was destroyed by

fire around 850, probably the result of a Viking raid.

Northumbrian

control of Galloway and Dumfriesshire was disrupted by the Vikings.

However, until the discovery of the Galloway Hoard, direct signs of

Viking power in the region were few and slight. These signs included

a Viking grave found in Kirkcudbright and Dublin Viking style houses

dated to the early eleventh century.

Few,

if any, locations in Dumfries and Galloway share the historic depth -

over 1500 years- of Whithorn as a continuously occupied settlement.

More typical of the ebb and flow of the region’s history is

Trusty’s Hill beside Gatehouse of Fleet. This hill fort is most

famous for its Pictish carvings.

Recent

careful analysis of the carvings has suggested that although inspired

by Pictish symbols the images on the stone were not carved by Picts.

One of the images (on right) shows , a ‘dragonesque’ creature

pierced by a spiked object, might be the Norse Fafnir; a greedy

dwarf who became a dragon and was killed by Sigurd.

Trusty’s

Hill rock carving

Kilmorie,

Ruthwell, Nithsdale, Whithorn and Trusty’s Hill are locations where

there was and still is good quality farm land. Such fertile soils

could produce a surplus of food, supporting the people who cultivated

the land as well as their churches and rulers.

Place

name evidence suggest that the Vikings, like the Northumbrians before

them, did not extend their settlements beyond the lower parts of

river valleys and the coastal fringe of Dumfries and Galloway.

However, the Viking Hoard was found well beyond the areas identified

as Scandinavian settlements by place name research.

On

the other hand, not far from where the Hoard was found, the medieval

castle of Threave still dominates the good quality farmland of

Balmgahie, Kelton and Crossmichael parishes. Threave is from the

Brittonic word ‘trev’, equivalent to the Scots ‘Mains’

meaning the home farm of an estate.

Threave

Castle- Historic Environment Scotland

But

there is nothing like the Kilmorie Cross at Threave, no imposing

Northumbrian monuments, no mysterious rock carvings like those on

Trusty’s Hill.

However,

among the treasures of the National Museum are the Torrs Pony Cap and

Carlingwark Cauldron. Along with the complex of Roman forts and

marching camps at Glenlochar, they are signs that Threave was ‘a

centre of paramount wealth and power’ 2000 years ago. The Romans

built their forts at Glenlochar to control the area. Archibald the

Grim followed the Romans when he chose Threave as the site for his

new castle in 1370.

Glenlochar

Roman fort

A

Viking warlord setting up camp in the district would therefore have

been able to draw on the long standing wealth of the land to feed

himself and his followers. No centre of Northumbrian power in the

district has been found, but the complex archaeology of the Hoard

find site might contain evidence of such a power centre, taken over

by Vikings.

The

survival untouched of the Galloway Hoard for over 1000 years suggests

its owner died elsewhere and never returned. Otherwise a Viking

kingdom may have emerged in the lower Dee valley.

Wigtownshire

did become part of a Viking kingdom. Its ruler was

Echmacarch

Rognvaldsson, described as ‘King of the Rhinns (of Galloway)’when

he died in 1165. Also known as Echmacarch mac Ragnaill, his

Viking-Gaelic kingdom included Whithorn but not eastern Galloway.

Echmacarch had previously been king of Dublin and the Isle of Man as

well.

In

852 an Irish monk described a new group of warriors fighting in

Ireland. These were the Gall-Ghaidheal. Gall, ‘foreigner‘ is the

word the Irish used to mean Vikings. Ghaidheal means

Gaelic-speaking. There are very few other mentions of these

Viking-Gaels in Irish records. The last time they appear is in 1234

when the death of Alan of Galloway ‘ri Gall-Ghaidheal’- king of

the Viking-Gaels - was recorded.

The

Gall part of Galloway also means ‘Viking’. The first

Viking-Gaelic king to rule all of Galloway was Alan’s

great-grandfather Fergus who reigned between 1110 and 1160. Fergus’

kingdom was only the southern part of a Gaelic speaking ‘Greater

Galloway’ which stretched north through Ayrshire into Renfrewshire

and east through Nithsdale into Annandale.

The

first district Fergus ruled was the lower Dee valley, either from

Kirkcudbright or, more likely, from a fortified base on Threave

island. Later Fergus’ kingdom grew westwards and northwards to

include the fertile lands of the Rhinns, Machars and Fleet valley

along with the livestock rearing and deer hunting districts of the

upland districts including Carrick in south Ayrshire.

While

Fergus was building his kingdom, King David I secured eastern

Dumfriesshire for his Scottish kingdom in 1124 by granting Annandale

to a Norman knight- Robert De Brus.

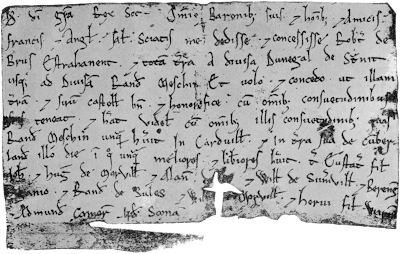

|

| Annandale Charter 1124 |

Fergus

had two sons, Gille-Brigte and Uhtred. After Fergus’ death in 1161,

they ruled jointly until 1174 when Gille-Brigte had his brother

gruesomely mutilated- blinded and castrated. Uhtred died of his

wounds, allowing Gille-brigte to rule alone until his death in 1185.

Gille-Brigte’s

grandson was Niall, Earl of Carrick. He had no male heirs so his

daughter Marjorie inherited Carrick. Marjorie was the mother of

Robert Bruce who became King of Scots in 1306.

Uhtred’s

grandson Alan had no male heirs. His youngest daughter Devorgilla of

Galloway was the mother of John Balliol who became King of Scots in

1292.

When

King Robert I died in 1329, his infant son became King David II. But

in 1332, King John Balliol’s son Edward seized the Scottish throne,

triggering a renewal of the Scottish Wars of Independence. Edward

Balliol died in 1367 and David II in 1371.

|

| Remains of Buittle castle, Balliol stronghold. |

Their

deaths did not quite bring Dumfries and Galloway’s Viking saga to

an end. King David II had been unable to control Galloway’s

Viking-Gaelic clans- the McDowalls, McCullochs and Mclellan’s.

Instead they transferred their loyalty to Archibald the Grim who

revived Fergus’ kingdom as a new, Douglas, Lordship of Galloway.

This

new lordship survived until 1455 when King James II finally secured

Galloway and its Gaelic inhabitants for the Scottish Crown. By 1560,

when John Knox preached the Reformation to the common people of

Galloway and Nithsdale, he was able to do so in Scots and Bible

English. 700 years of Viking-Gaelic heritage had finally and silently

faded away.

|

| Lands taken by James II in 1455 from last Lord of Galloway |