Gaelic and Land Use Part One

Gaelic

and land use. Part One.

As

I have been writing this post, I have realised it covers a huge

area-physically and historically. What I have done is stopped halfway

through the more detailed section, where I am trying to work out how

many people would have lived on the remote upland farms where Gaelic

will have lingered longest.

The

same information can be used to get idea of the ratio of upland to

lowland population distribution, including proximity to the burghs/

towns where we know Scots had become established by 1500. Once I have

done this, it will become Part Two of this post.

Thinking

about the shift from Gaelic to Scots as the language of Galloway,

key questions are when and how did Scots achieve ‘critical mass’?

By critical mass I mean a tipping point where the majority of the

population had become Scots speakers and Gaelic became the language

of a minority.

As

I have discussed previously, there is written evidence that Scots

rather than Latin was used as the administrative language of the

Douglas lordship of Galloway from the 1390s and of the baron court of

Whithorn priory by 1438. The Wigtown Burgh Court Book records from

1513 to 1536 show the use of Scots. The Kirkcudbright burgh records

only survive from 1576, but are also in Scots. The Stranraer burgh

records date from 1588 and again are in Scots.

Ayr

became a royal burgh in 1205. The Ayr burgh accounts 1534-1624 . They

were transcribed and published in 1936.

Dumfries

became a royal burgh in 1186. The local archives have burgh records

dating back to 1395.

Burghs

were administrative and market centres for surrounding areas. They

were also part of the advance of feudalism in Scotland, where land

ownership derived from royal charters - for example king David I

charter of 1124 which confirmed the ownership of Annandale by the

Bruce family. The burghs were the first towns in Scotland. The burghs

were places where the Scots language developed and spread from.

Whithorn

was an exception, since it had become a town-like industrial and

trading centre by the eleventh century with Irish Sea Viking

connections. Whithorn had been an important religious centre since

the fifth century. Kirkcudbright may have its origins as a Viking era

trading centre.

Whithorn’s

importance as a religious centre has been the subject of

archaeological investigation. This provides an insight into land use

in the surrounding area of the Wigtownshire Machars. A significant

discovery made at Whithorn was the use of plough pebbles between the

sixth and ninth centuries. Plough pebbles are small hard stones used

to give wooden ploughs a better cutting edge. The Whithorn plough

pebbles were a surprise, since they were 500 years older than

previous examples found. [DGNHAS 1990]

|

| Plough pebbles from Yorkshire |

When

the plough pebbles were in use, the local language would have been

Brittonic and then the Old English of the Northumbrian church at

Whithorn. Gaelic would have arrived in the Machars when it became

part of the Irish Sea Viking world in the tenth century. The

Viking-Gaelic Gall-Ghàidheil arrived by a different route, probably

originating in Argyll before moving east and south into Ayrshire and

then Galloway.

Two

place name elements -airigh and eileirg, found locally as arie or

airy and elrig or elrick - are both Gaelic and indicate land use.

Airigh in Scots Gaelic meant ‘summer pasture’, areas where

livestock were grazed on moor and hill land during the summer months.

Eileirg means a deer trap, natural features wider at one end than the

other which deer could be driven into and then killed.

In

Mochrum parish on the west side of the Machars peninsula, on the edge

of an area of poorer quality land, the farms of Airylick and

Airyolland are adjacent to Eldrig loch, fell and farm. The eileirg

would have been on Eldrig Fell which then gave its name to the farm

and loch. Further east in Kirkinner parish, Whithorn Priory owned the

farms of Meikle and Little Airies.

|

| Map key: blue dots, Priory of Whithorn lands. Red E -eileirg Red X - airigh farms Yellow M - mottes Purple L- Lordship of Galloway farms. |

Previously

ruler of Viking Dublin, at the time of his death in 1065, Echmacarch

Mac Ragnall was described as ‘king of the Rhinns’. The territory

he ruled included Whithorn and the Machars as well as the Rhinns of

Galloway.

The

people who were to give their name to Galloway were the

Gall-Ghàidheil. See Clancy, T.O. (2008) The Gall-Ghàidheil and

Galloway. Journal of Scottish Name Studies(2), pp. 19-50.

In

1128, Gilla Aldan was installed as the Bishop of Whithorn, probably

at the instigation of Fergus of Galloway. Although Fergus was not

described (or even mentioned?) in the Annals of Ulster as king of the

Gall-Ghàidheil, his great-grandson Alan was described as such by the

Annals at his death in 1234.

The

implication being that sometime between 1065 and 1128, the

Gall-Ghàidheil became the dominant power in Galloway and Gaelic the

dominant language. Under the rule of Fergus and his descendants, for

the first time Galloway emerges as a distinct and important

kingdom/province, with Whithorn as its religious centre.

The

wealth and power of Galloway’s medieval rulers came from the land

and the people it supported. The more effectively the land was used,

the greater the wealth and power of its rulers. The airigh and

eileirg place names, which are found in the Rhinns of Galloway,

across the main Galloway uplands, on the slopes of Cairnsmore of

Fleet, Screel/Bengairn and Crifell hills as well as the Machars, show

how the resources of the poorer quality soils were used.

The

use of plough pebbles had ended before the kingdom/lordship of

Galloway emerged. However, the link between religion and agricultural

improvement was continued with the plantation of abbeys (as well as

priories and a nunnery) across Galloway by Fergus and his successors

in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Cistercians at

Dundrennan, Glenluce and New Abbey (Holm Cultram in Cumberland also

had land in Galloway) were the main beneficiaries with the

Premonstratensians at Whithorn, Saulseat and Tongland while Lincluden

was a Benedictine nunnery.

In

parallel with grants of land to the Church, lowland Galloway is

dotted with many Norman style mottes (pudding shaped earth mounds)

showing where non-religious grants of land were made. Some may have

been built by existing, Gaelic speaking, landowners. The others were

built for the Scottish or northern English descendants of Normans.

For example the motte at Sorbie in the Machars [on map above] was

built for the de Vieuxpont family of Westmorland who were related by

marriage to the de Morvilles, also from Westmorland. Richard de

Morville’s daughter Elena was married to Roland / Lachlann, Fergus

of Galloway’s grandson.

The

mottes were not part of a ‘Norman conquest’ of Galloway. They can

best be seen, along with the abbeys, as an attempt to ‘modernise

and improve’ Galloway by its rulers. A key technological

development was the introduction of heavy, oxen drawn ploughs. These

were made of wood, but used iron rather than pebbles along the

cutting edge. [Note: I have tried to find a date for the

introduction of these ‘new’ ploughs in Galloway. The nearest I

have found is a link between the de Moreville family and ‘plough

irons’ at Lauder in south east Scotland circa 1170.]

The

new ploughs allowed more land to be cultivated, increasing the amount

of oats and barley which could be grown. By increasing the surplus of

arable crops produced in the lowland areas, it was possible to

support more livestock-cattle, sheep, horses and goats -farmers in

the uplands. The distribution of the Lordship of Galloway lands

recorded in 1456 show a mix of lowland and upland farms which would

have facilitated the integration of arable and livestock farming.

The pattern persisted. Writing in the 1680s, Andrew Symson of

Kirkinner parish stated that

[Minnigaff

village] hath a very considerable market every Saturday, frequented

by the moormen of Carrick, Monnygaffe, and other moor places, who buy

there great quantities of meal and malt, brought thither out of the

parishes of Whitherne, Glaston, Sorbie, Mochrum, Kirkinner &c.

[Large Description of Galloway, Edinburgh, 1823]

Did

the motte makers settle English or Scots speaking tenants /peasants

equipped with new and improved ploughs and teams of oxen around their

’caputs’? The motte near Gelston parish is on the farm of

Ingleston (Ingles / Inglis = English). There are Inglestons near

mottes in Borgue, New Abbey and Twynholm parishes as well. However,

other Ingleston farms in Irongray and Kirkgunzeon parishes are not

near mottes, although they are near older (Iron Age) forts. Most

Galloway mottes do not have Inglestons near by.

For

the central Stewartry I have mapped the mottes and the nearest farms

with Gaelic names.

|

| Gaelic farms green * plus mottes |

On

arable farms, the need to use a team of six or eight oxen to plough

the land led to multiple tenancies, with each tenant owning an ox or

having a part share in an ox. Arable farming was labour intensive. To

extend the area of arable farming required population growth.

Scotland experienced a period of warmer and drier conditions from the

twelfth to fourteenth centuries. This would have increased crop

yields so the people, including children were better fed and more

likely to survive childhood. This led to population growth.

With

more people available to work the land, the area under arable

cultivation could be increased, producing more food and further

population growth. By the beginning of the fourteenth century then,

Galloway’s arable lowlands would have supported what would have

been historically its largest population- and who would have been

Gaelic speakers. The upland farms would also have been occupied by

Gaelic speakers, but relatively fewer.

Unfortunately,

apart from a rental roll for Buittle parish from 1374, there is no

detailed information about the population of Galloway until 1684. In

that year, as part of attempts to suppress dissident Covenanters, a

list of all the inhabitants of Wigtownshire and Minnigaff over the

age of 12 was drawn up by parish ministers.

At

741, Minnigaff in the Stewartry had the highest population, but at

140 square miles it was also the largest parish so had a population

density of only 5 people (over the age of 12) per square mile.

Sorbie parish in the Machars had a population of 437 and an area of

15 square miles, giving it a population density of 29 people (over

the age of 12) per square mile.

Kirkcowan

parish has an area of 56 square miles and had a population of 491 in

1684, giving 9 people (over the age of 12) per square mile. In the

northernmost part of Kirkcowan was the

Barony

of Sleudinle. It covered approximately 10 square miles and had 55

inhabitants over the age of 12. It contained the highest hill in

Wigtownshire, Craigairie, 1050 feet.

|

| Barony of Sleudinnle |

1.

Barrnbrake (2)

Rodger

McQuaker

Janet

Wilson

2.

Craigairy (3)

James

Stroyen

Mart.

McChiney

Janet

Milroy

3.

Alderickallabrichan (4)

William

McCa

Janet

McTear

Gilbert

McCa

Mart.

Heron

3.

Highdirry (5)

Tho.

Milweyen

Marion

McCa

Helen

McClemin

Pat

McBride

Janet

McQuaker

4.

Laigdirry (5)

John

McLure

Janet

McMiken

Marion

Walker

Janey

Milroy

Tho.

McNily

5.

Craigmuddy (6)

Robert

Mcnily

Janet

Kie

James

McNily

Katherin

McNily

Mart.

McNily

Mart.

McQuaker

6.

Killyalkirk (5)

Gilbert

McLaughlen

Gilbert

McKibbon

Marion

McWilliam

And.

McLaughlen

Isobell

Blain

7.

Dirvannay (4)

James

Stroyen

Chirstian

McMurry

Alexr.

Stroyen

Janet

Stroyen

8.

Munondowy (3)

George

McMurry

Anaple

McCa

Janet

McMurry

9.

Dirvaghly (4)

John

McTear

Janet

McMurry

Henry

Wallace

Marion

Wallace

10.

Dirnark (3)

John

McMurry

Isobell

McLaughlen

Gilbert

McMurry

11.

Aldericknair (6)

Alexander

Kie

Janet

Mochoule

Janet

Heron

John

Stroyen

Janet

McWilliam

Mart.

McCraich

12.

Nether Alderick (3)

Gilbert

McCraken

Janet

Stewart

Robert

McCracken

13.

Inshanks (2)

Robert

McCraken

Janet

McKuinn

As

Sleudunnull, the Barony of Sleudinle is included in the list of lands

forfeited to the Scottish Crown by the Douglas Lordship of Galloway-

Exchequer Rolls Vol. VI 1456, page 193 - 'Et de xv li. de firmis

terrarum de Sleundunnull.'

The

northernmost part of Minnigaff parish was the Forest of Buchan,

covering roughly 40 square miles, containing 11 farms and 46

inhabitants over the age of 12. The Forest of Buchan included the

highest hill the south of Scotland, Merrick at 2677 feet. Before

1455, Forest of Buchan belonged to Douglas Lordship of Galloway.

1.

Palgouen (6)

John

M'Kie in Palgouen

Elizebeth

Dunbar, his spouss.

Alexr.

McTier there.

John

Mcjampse there.

Grisell

McClelland there.

John

McKie there.

2.

Kirkcastle (4)

Michael

McTagart in Kirkcastle.

Cathren

Gordan, his spouss.

Alexr.

M'Goun.

Grisell

Wilson, his spouss.

3.

Kirriereoch (4)

Gilbert

McCutchen in Kirrireoch.

Marron

McKie, his spouss.

Pattrick

McClelland.

Janet

McMillan, his spouss.

4.

Kirrimoir (11)

John

McGoun in Kirrimoir.

Janet

McClamont, his spouss.

Hilling

McGoun there.

Rott.

Gordon.

Isobell

McClamont, his spouss.

John

McClamont.

John

Jamieson.

Patt

McCluire.

Janet

Thomson.

Jaen

Murray.

Janet

Cairnes.

5.

Kirriekennan (2)

Gilbert

McKie in Kirriekennan.

Jaen

McKie, his spouss.

6.

Kilkerrock (4)

John

Gordan in Kilkerrock.

Jealls

Gordan, his spouss.

Margrat

Findly there.

Alexr.

Gordan there.

7.

Stroan (6)

John

McMillan in Stroan.

Jaen

Heroun, his spouss.

Antony

Wilson.

Isobel

McGoune.

Androu

Gordan.

Cathrain

McClurge.

8.

Eskeunhan (2)

John

McKie in Eskeunhan

Grisel

Milroy, his spous

9.

Kirauchrie (2)

James

Murray in Kirauchrie.

Hilling

Gordan, his spouss.

10.

Glenheid (2)

James

Gordan in Glenheid.

Jaen

McMillan, his spouss.

11.

Buchan (3)

Thomas

Gordan in Buchan.

------

McCutchen, his spouss.

-------

McYelvour there.

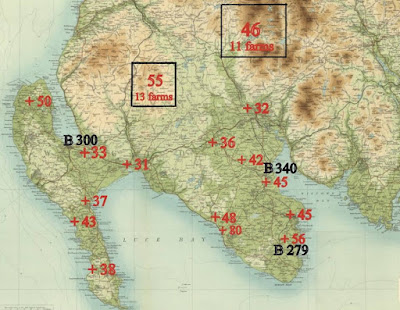

B = burgh with population. Red + individual farms with number of inhabitants. Black boxes show Sleudinnel and Forest of Buchan.

The

map is an attempt to illustrate the greater population density of

the mainly arable farming lowlands. Once Scots had become the

everyday language of the thousands who lived in the more densely

populated parishes, it would have been difficult for Gaelic to

survive among the hundreds who lived in the more thinly populated

uplands.

The

natural lines of communication, river valleys and passes, run

north-west to south-east. A community of Gaelic speakers in and

around the Barony of Sleudinnle would have been isolated from a

similar community in the Forest of Buchan who in turn would have had

a difficult journey over the hills to Carsphairn.

I

am now slowly going through the Wigtownshire and Minnigaff Parish

Lists 1684 parish by parish, looking at the relative distribution of

small (1-10 occupants) middle sized (11-20 occupants) and large (21 +

occupants) farms.

For

the northern parishes containing upland areas the results are:

Inch

[50 square miles, 625 persons, 175 = 28% in upland area]

54

small, 16 middle sized, 3 large farms.

Glenluce

[98 square miles, 614 persons]

56

small, 19 middle sized, 7 large farms.

Kirkcowan

[56 square miles, 491 persons]

62

small, 11 middle sized, 1 large farms.

Penningham

[54 square miles, 589 persons]

42

small, 12 middle sized, 6 large farms.

Minnigaff

[140 square miles, 741 persons]

72

small, 17 middle sized and no large farms

For

comparison:

Glasserton

in the Machars [22 square miles, 423 persons]

7

small, 17 middle sized and 4 large farms.

Kirkinner

in the Machars [28 square miles, 628 persons]

22

small, 21 middle sized and 6 large farms.

Kirkcolm

in the Rhinns [22 square miles, 501 persons]

8

small, 11 middle sized and 4 large farms.

Kirkmaiden

in the Rhinns [23 square miles, 621 persons]

15

small, 9 middle sized and 14 large farms.